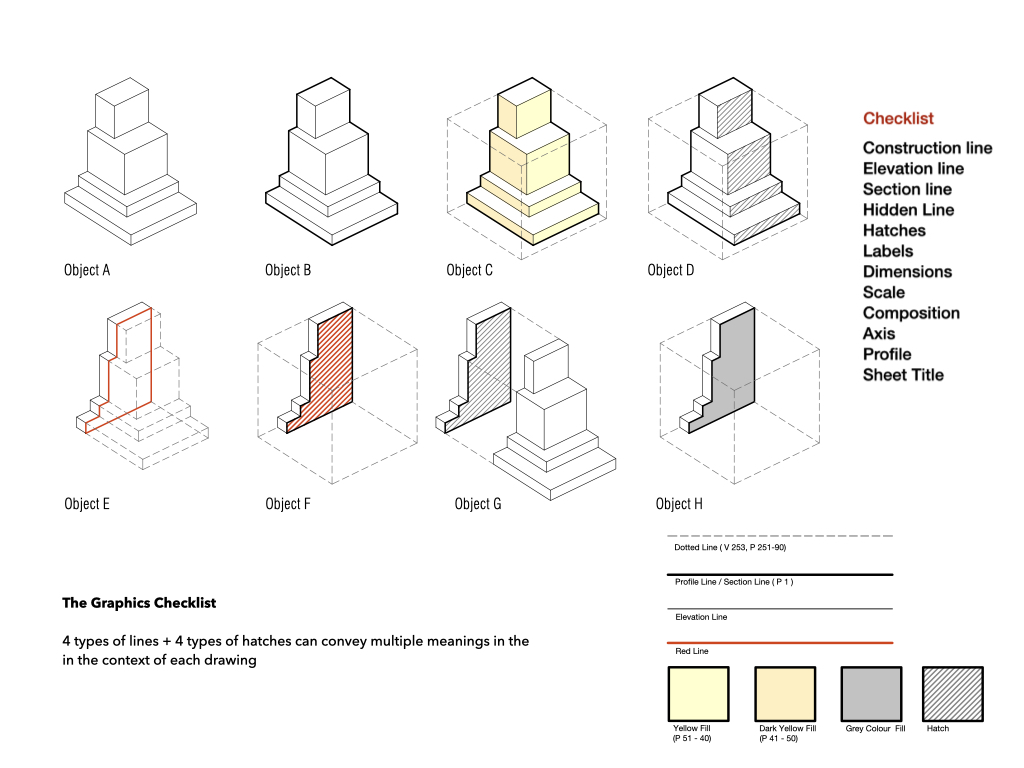

Checklists are the opposite of playlists (which I discussed in a previous blog post). This image above is from my tagboard at college, and the drawing in the center is the ‘Graphics Checklist’. It is a drawing checklist I made many years before and have been using consistently since then. While playlists are playful and flexible, checklists can feel dry, nerdy, and dull. But I appreciate them greatly and use them frequently in my teaching, to the point that my students may grow wary of them. My attachment to checklists likely stems from the frustration of repeatedly teaching basic drafting skills to first-year students and having to reinforce the same principles all the way through their thesis—and often in between.

To streamline this, I introduce the concept of a checklist in their first-semester drafting class and continue to use it as a reference tool whenever I meet them over the next five years. It’s not that these drawing conditions are hard to apply; they’re just easy to forget. Wittgenstein writes “The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity.” We all rely on checklists, especially when we travel, and in many other contexts. They guide critical processes, from prepping an airplane for takeoff to setting up an operating theater or packing for a trip. Checklists are invaluable.

The book The Checklist Manifesto is one of the trigger to consolidate the fragmented rules into a single and visible narrative. This book is a great narrative on the simple need of lists and how they can be life saving (not exaggerating) – It traces the the birth of the checklist from the early plane (bombers), construction industry, etc. In the book , Gawande writes

“Substantial parts of what software designers, financial managers, firefighters, police officers, lawyers, and most certainly clinicians do are now too complex for them to carry out reliably from memory alone.”

“In a complex environment, experts are up against two main difficulties. The first is the fallibility of human memory and attention, especially when it comes to mundane, routine matters that are easily overlooked under the strain of more pressing events. (When you’ve got a patient throwing up and an upset family member asking you what’s going on, it can be easy to forget that you have not checked her pulse.) Faulty memory and distraction are a particular danger in what engineers call all-or-none processes: whether running to the store to buy ingredients for a cake, preparing an airplane for takeoff, or evaluating a sick person in the hospital, if you miss just one key thing, you might as well not have made the effort at all.

A further difficulty, just as insidious, is that people can lull themselves into skipping steps even when they remember them. In complex processes, after all, certain steps don’t always matter. … “This has never been a problem before,” people say. Until one day it is.

Checklists seem to provide protection against such failures. They remind us of the minimum necessary steps and make them explicit. They not only offer the possibility of verification but also instill a kind of discipline of higher performance.”

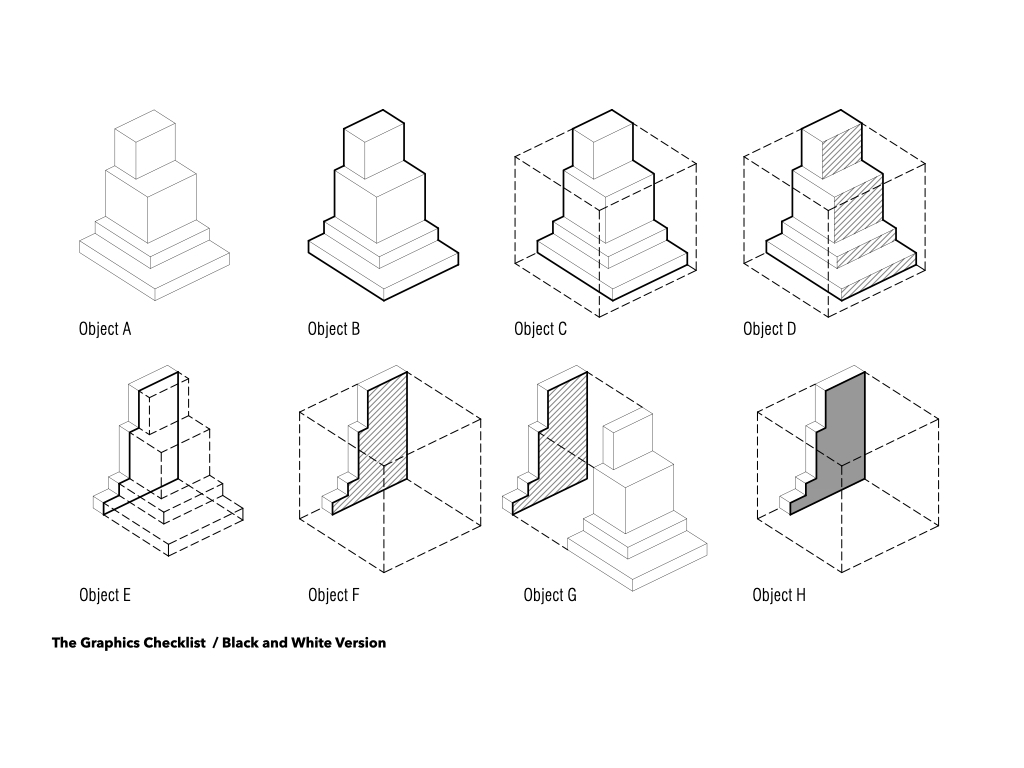

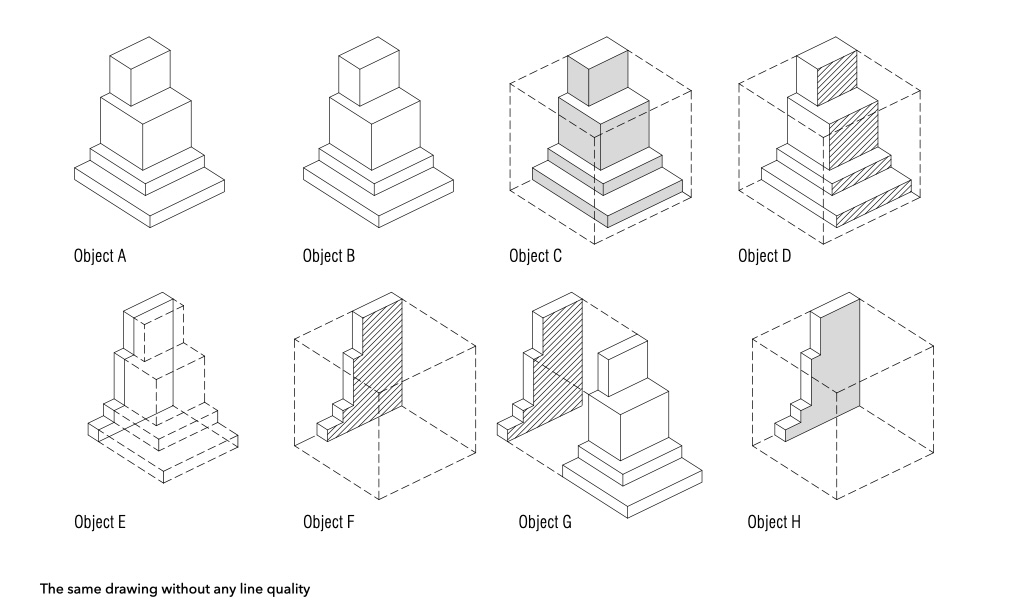

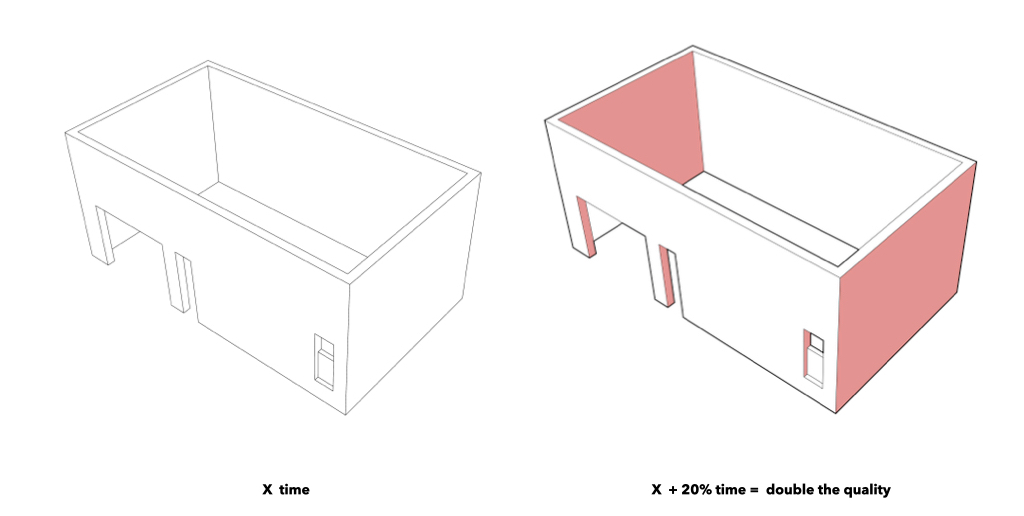

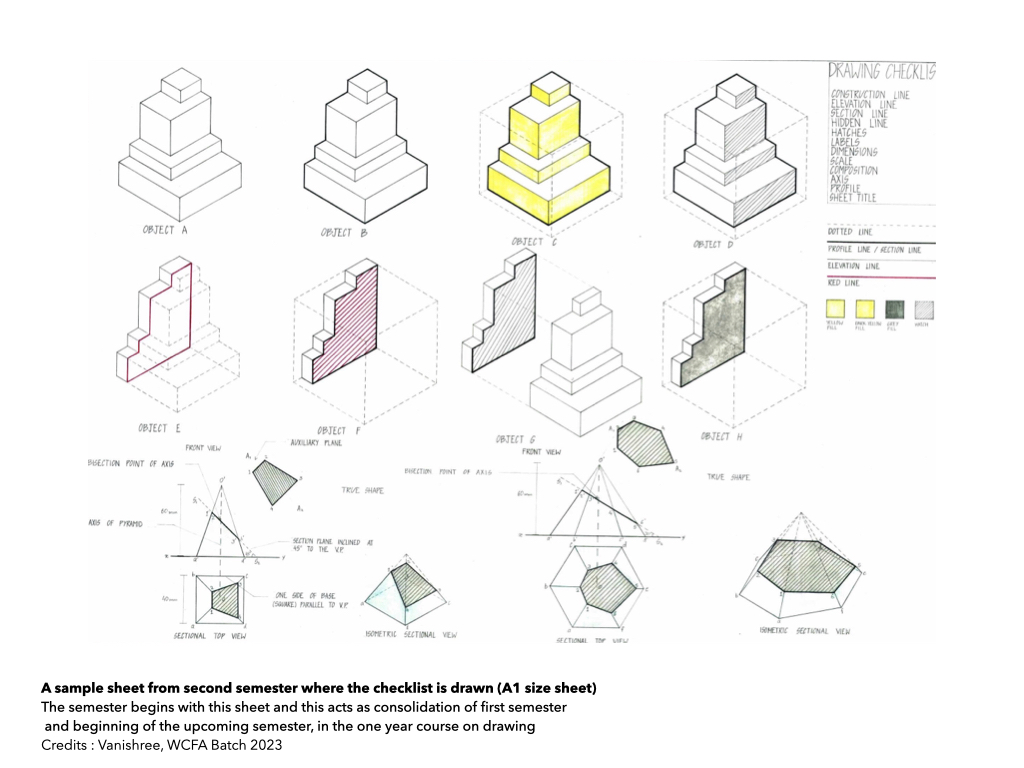

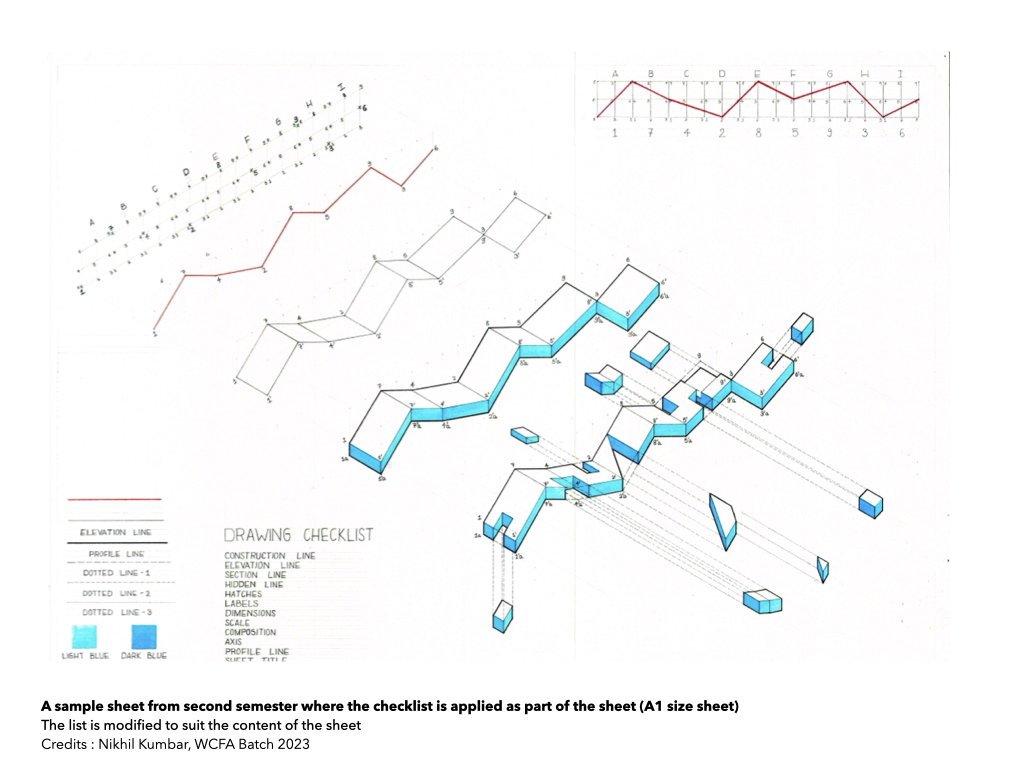

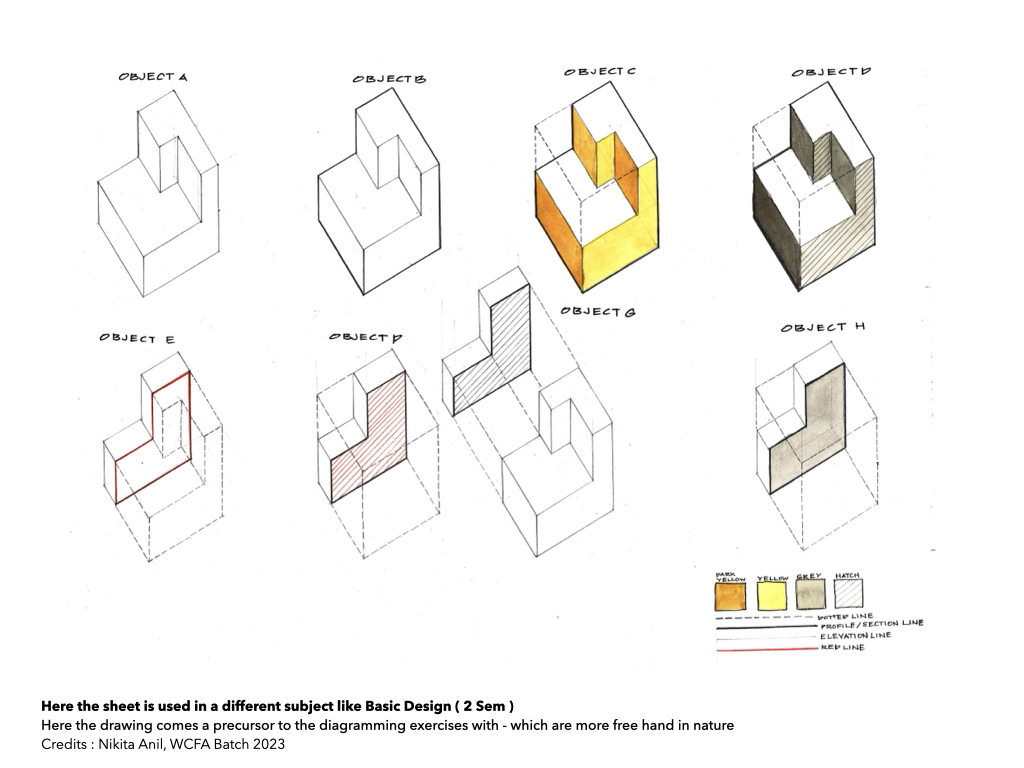

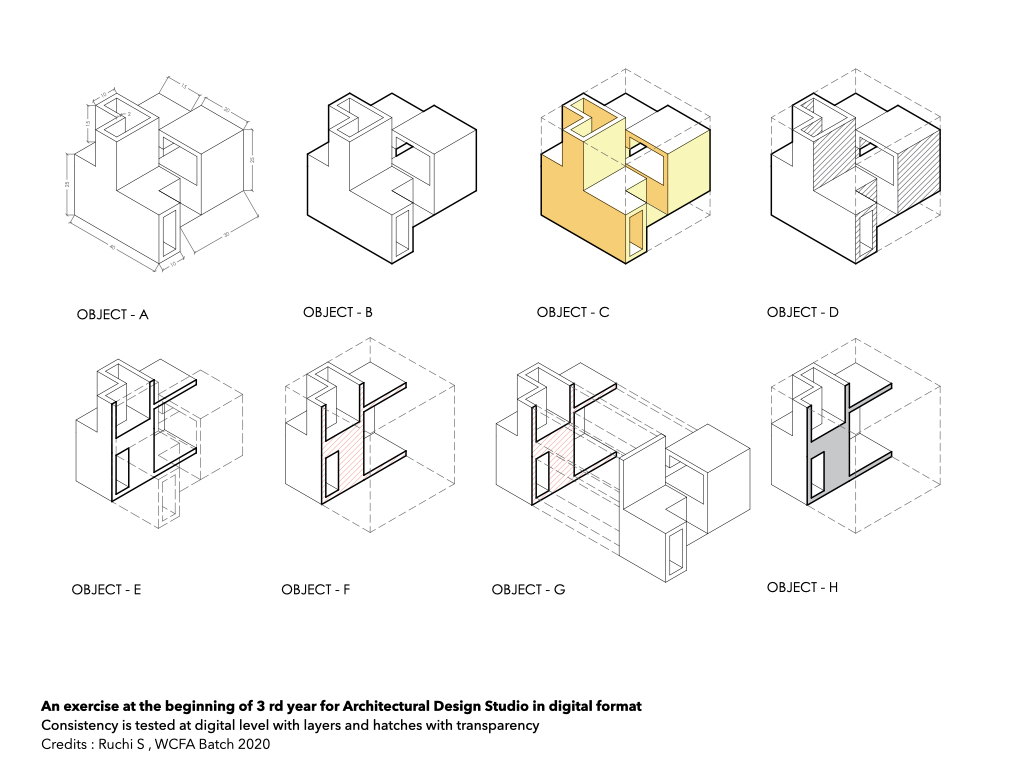

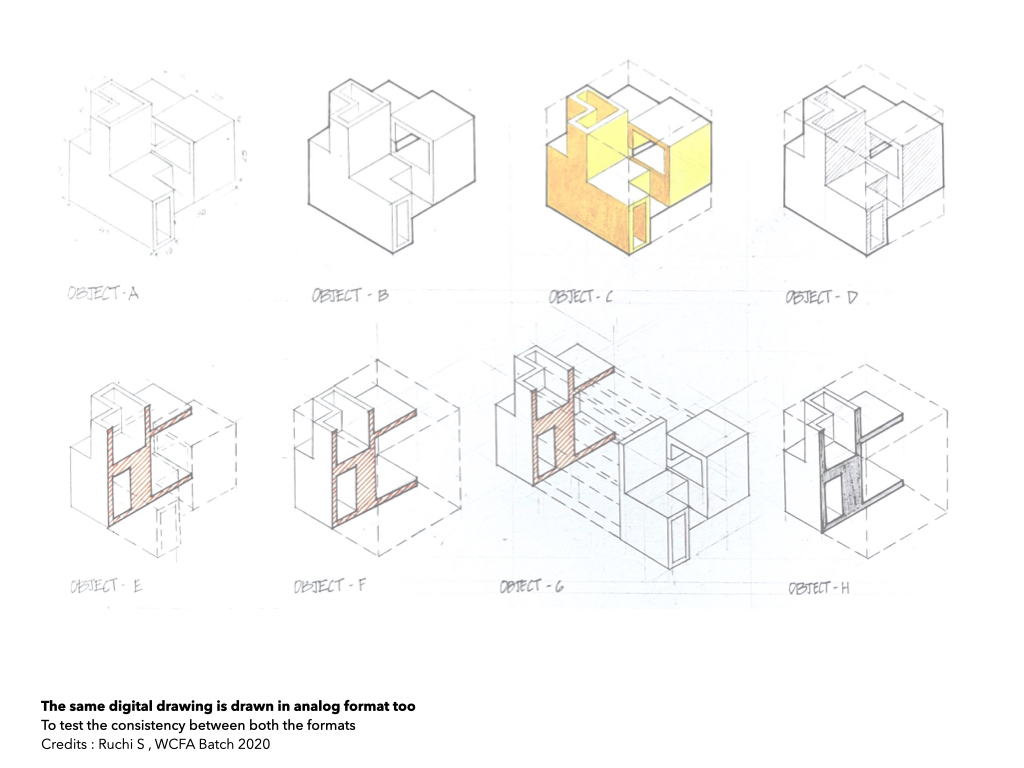

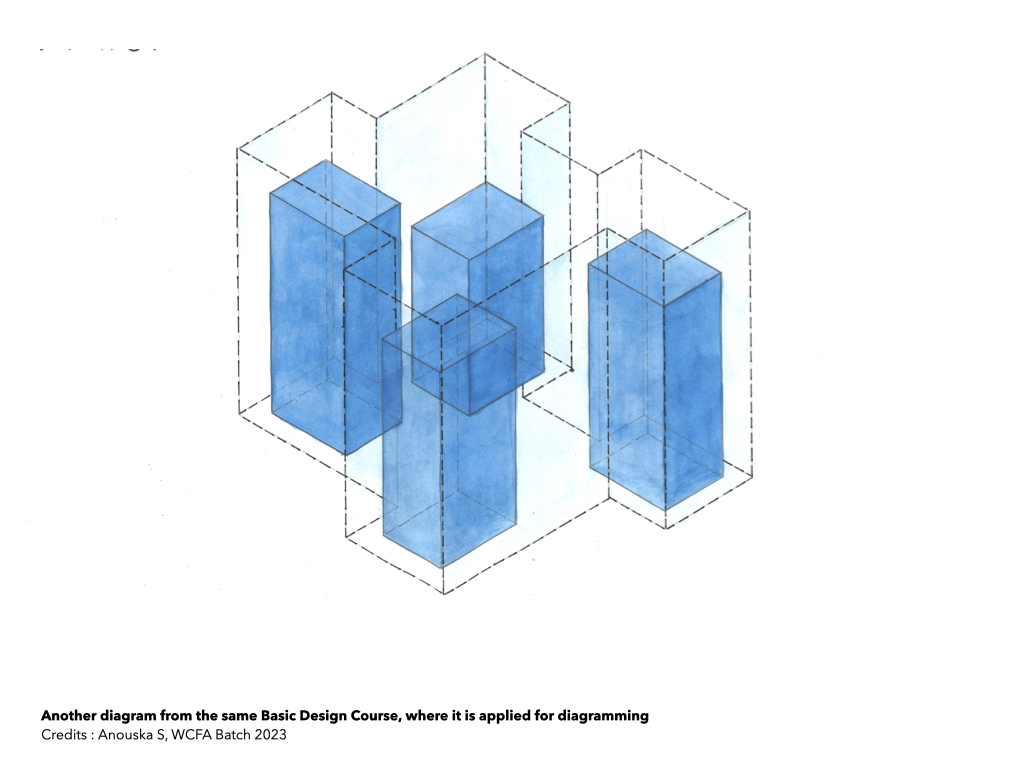

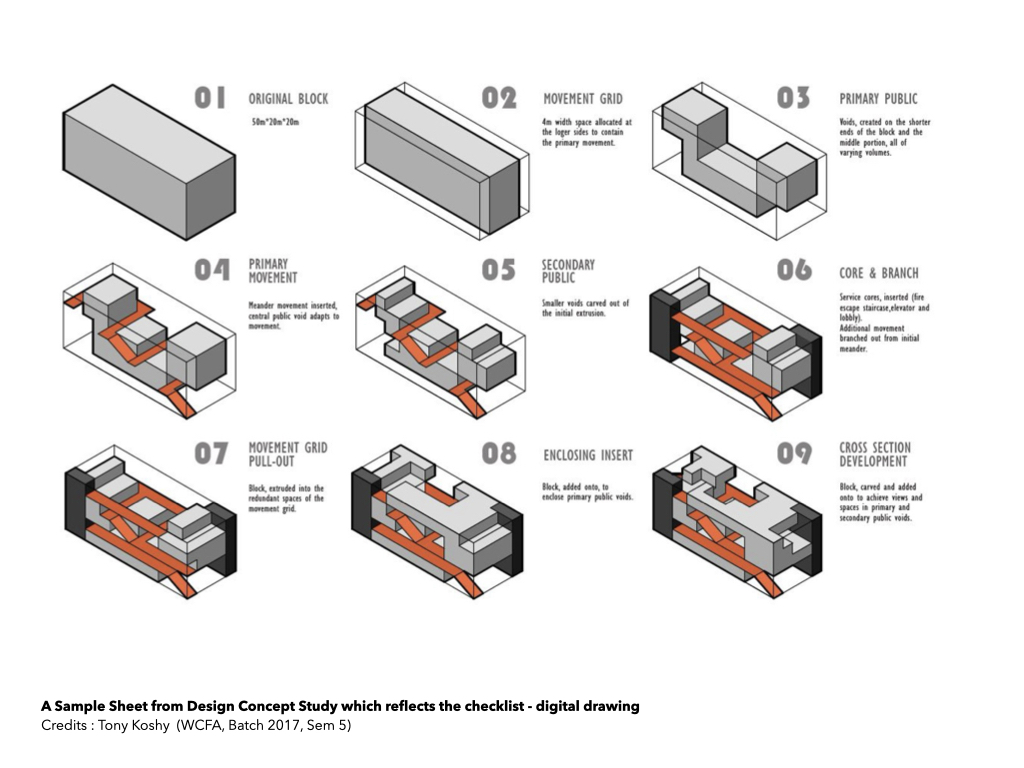

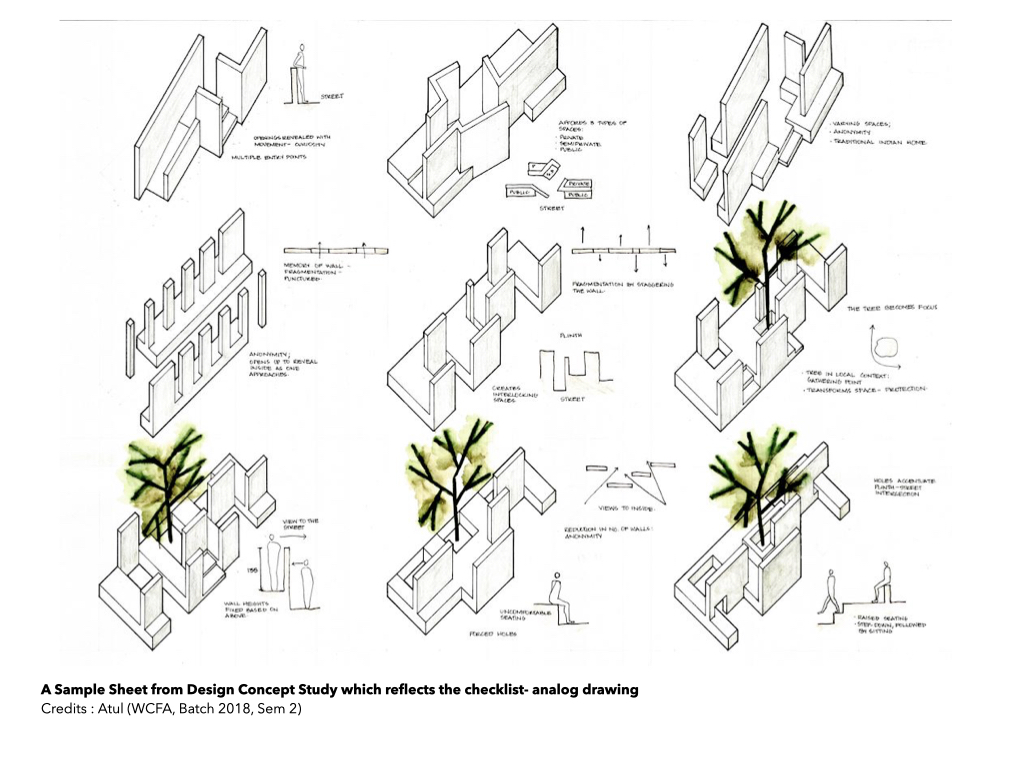

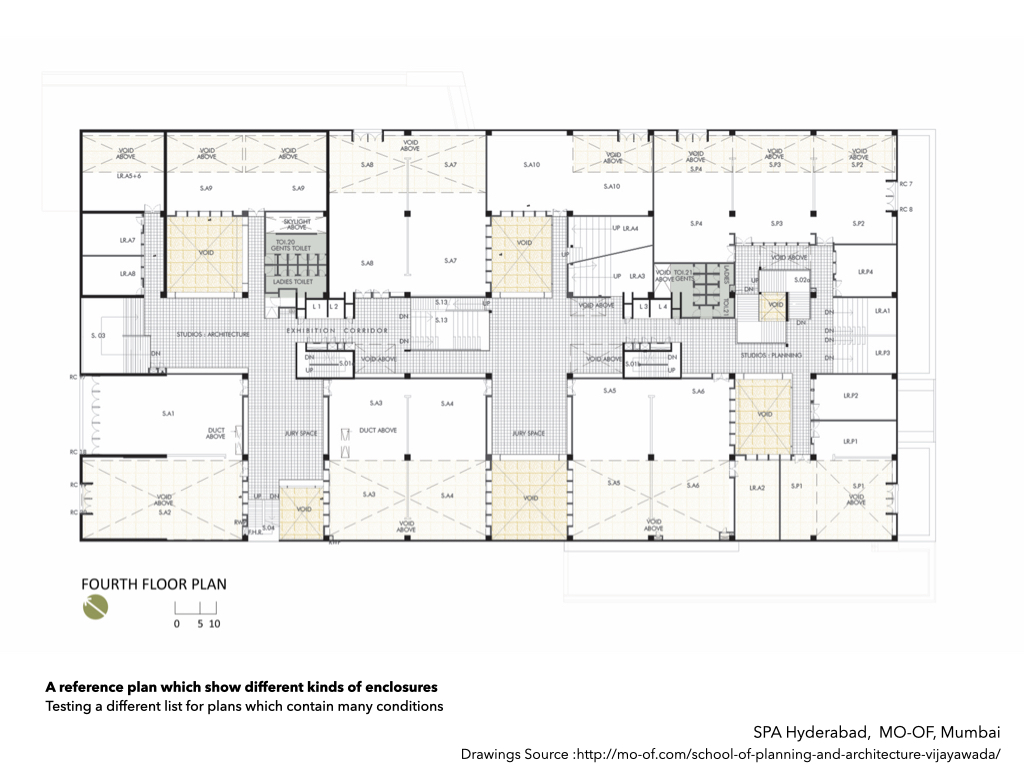

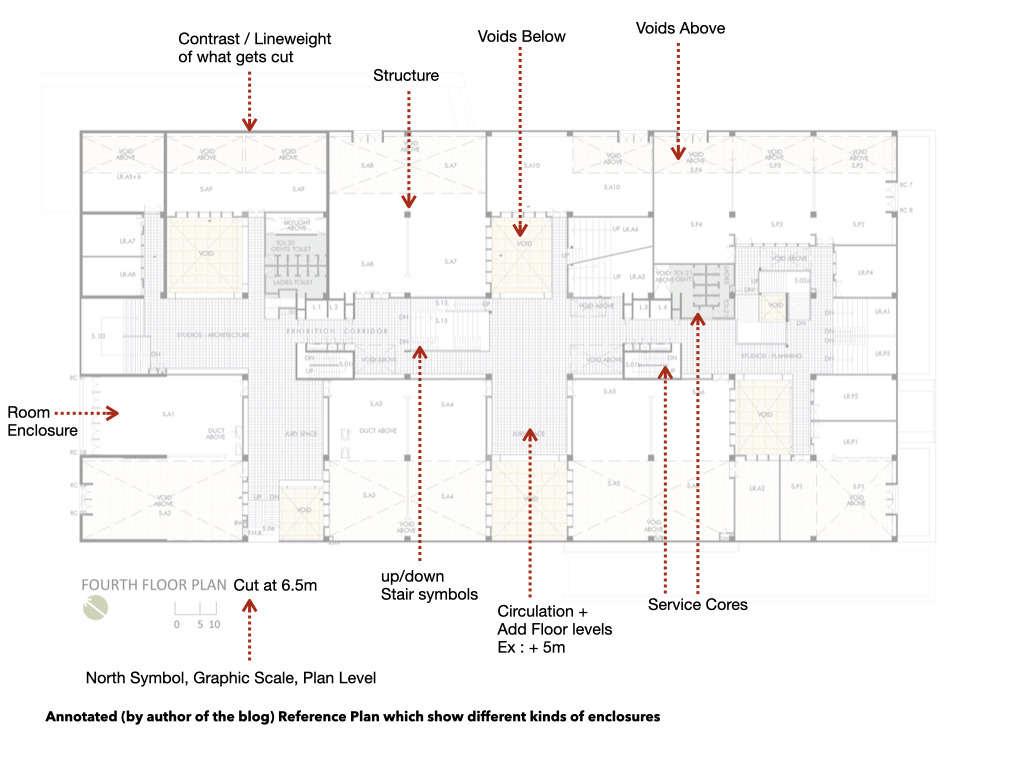

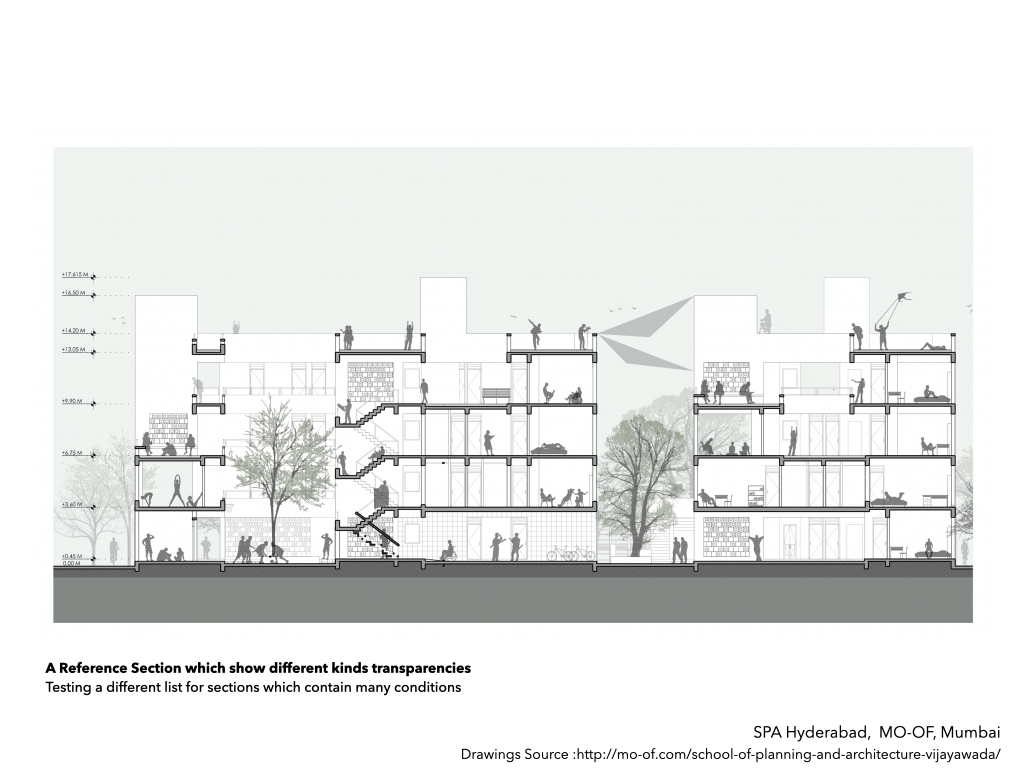

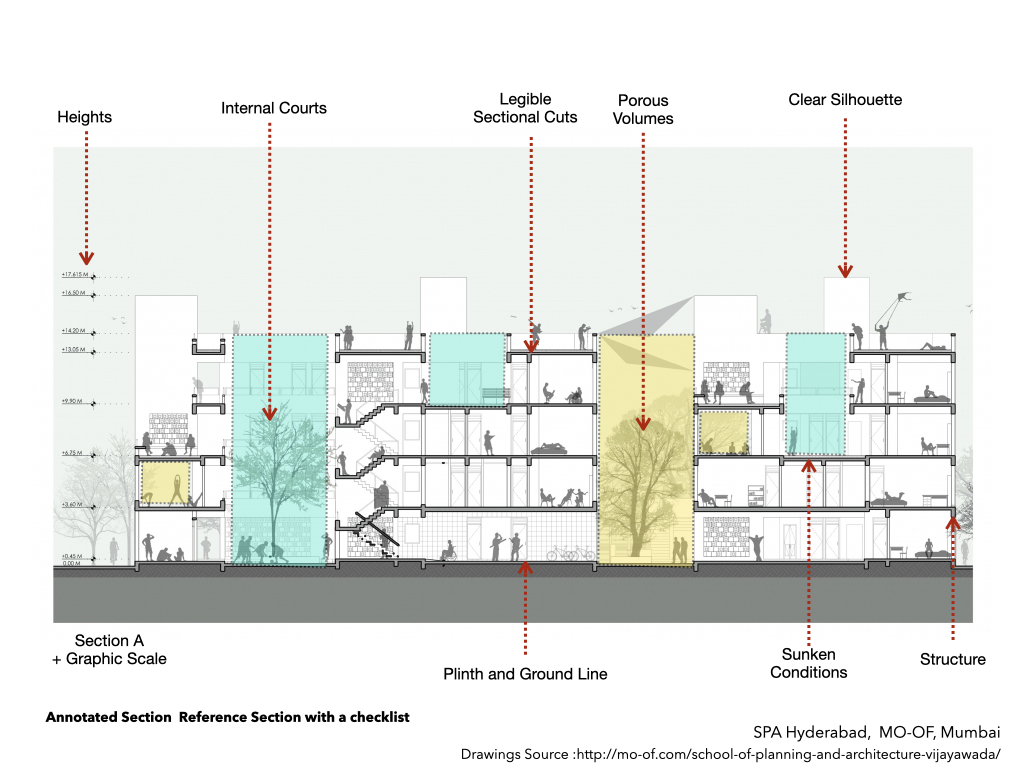

Below is the Graphics Checklist and many variations and reflections in student works at WCFA of it over the years – tested from first year drafting to various other semesters in different forms. Unless credited all the drawings are made by the author of the blog.

You must be logged in to post a comment.