“Some books should be tasted, some devoured, but only a few should be chewed and digested thoroughly.” Francis Bacon

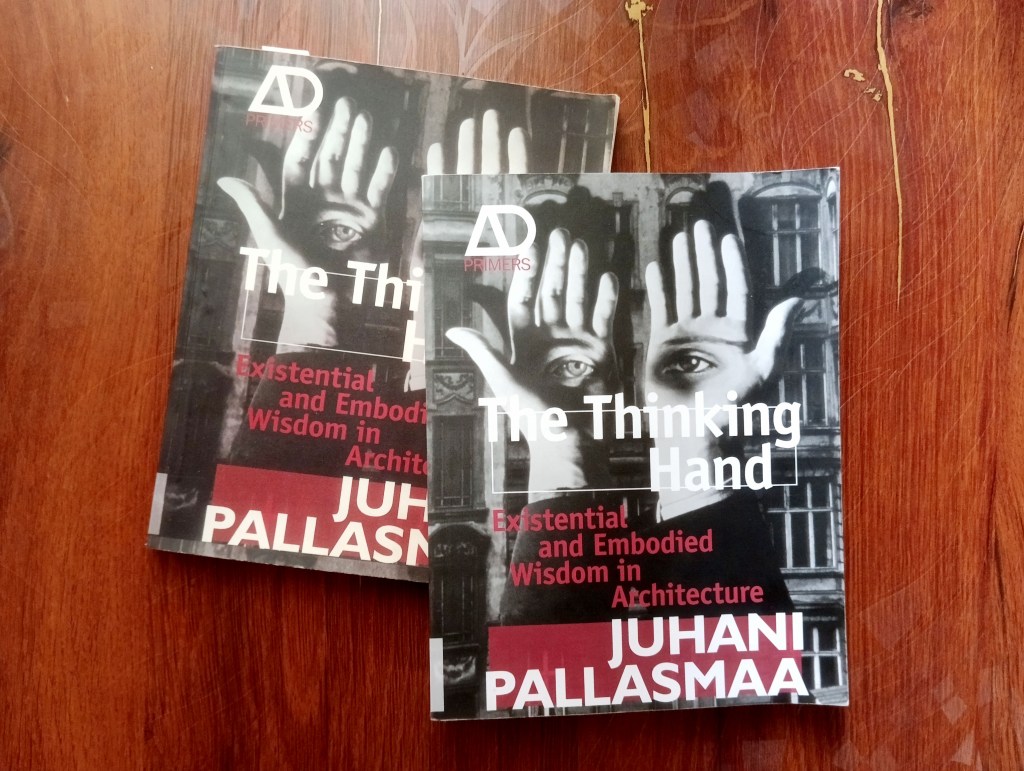

I have 2 copies of Juhani Pallasmaa’s ‘The Thinking Hand’. One of the few (or may be the only one) books on architecture i have read from the first page to the last page. A book very close to me. It has sustained 13 years of interest. Pallasmaa’s ‘The Eyes of the Skin’ is a more frequently read and referenced text . If you are an admirer of that text, this book is a great continuation.

The first one I read in 2010. I was in my third semester at the Theory and Design Master’s Program at CEPT. And it had taken almost the first year of my course to make reading a prominent part of my learning curve. I had read very less as an undergrad student. This book had just been published then and had arrived at CEPT library. After reading the library copy, i bought a copy to myself so that i can underline it and add my notes. It is in that mood i had read the book voraciously. I have to admit here, that the first copy is a photocopy. I think it costed me 300 bucks. The ‘xerox’ shop at CEPT made a wonderful job of photocopying book for the students. Most humane form for breaking the law i guess – by sharing knowledge. If you take a quick glance at the book now , you won’t make out that it is a photocopy. Even the cover is laminated colour photocopy. Unless someone has seen the original, this is good enough.

I recently (2022) bought the original book at ten times the cost. Still very expensive. I always felt guilty reading the photocopy, as i have been rereading parts of it for last 13 years! and i I have merrily ‘extracted’ a lot of quotes for my lectures and essays. This book puts in perspective for me on what is the role of architectural theory – its limits and possibilities. It is brilliantly articulated in these two phrases : “the discipline of architecture has to be grounded on a trinity of conceptual analysis, the making of architecture, and experiencing” and “whereas a theoretical survey that is not fertilised by a personal encounter with the poetics of building is doomed to remain alienated and speculative”.

By the way i have underlined notes in these two books, I can see my two different selves between the two books. Even though the first self is more ideal, optimistic than the sober, bit worn down academic; i am comforted to know i have highlighted similar sentences between both the versions and the consistence of my inclination towards certain ideas which still keep me going.

Below are a selection of my highly revisited quotes from my ‘extracts’ (all bold emphasis mine):

1.

“In my view, the discipline of architecture has to be grounded on a trinity of conceptual analysis, the making of architecture, and experiencing – or encountering – it in its full mental, sensory and emotional scope. The point that I wish to emphasise is that an emotional encounter with architecture is indispensable both for creating meaningful architecture and for its appreciation and understanding. Design practice that is not grounded in the complexity and subtlety of experience withers into dead professionalism devoid of poetic content and incapable of touching the human soul, whereas a theoretical survey that is not fertilised by a personal encounter with the poetics of building is doomed to remain alienated and speculative – and can, at best, only elaborate rational relationships between the apparent elements of architecture.” (146)

2.

“In addition to operative and instrumental knowledge and skills, the designer and the artist need existential knowledge moulded by their experiences of life. Existential knowledge arises from the way the person experiences and expresses his/her existence, and this knowledge provides the most important context for ethical judgment. In design work, these two categories of knowledge merge, and as a consequence, the building is a rational object of utility and an artistic/existential metaphor at the same time.

All professions and disciplines contain both categories of knowledge in varying degrees and configurations. The instrumental dimensions of a craft can be theorised, researched, taught and incorporated in the practice fairly rationally, whereas the existential dimensions are integrated within one’s own self-identity, life experience and ethical sense as well as one’s personal sense of mission. The category of existential wisdom is also much more difficult to teach, if not outright impossible. Yet, it is the irreplaceable condition for creative work” (119)

3.

“The great gift of tradition is that we can choose our collaborators; we can collaborate with Brunelleschi and Michelangelo if we are wise enough to do so” (146)

4.

“Drawing is an observation and expression, receiving, at the same time. It is always a result of yet another kind of double perspective; and giving a drawing looks simultaneously outwards and inwards, to the observed or imagined world, and into the draughtsman’s own persona and mental world. Each sketch and drawing contains a part of the maker and his/her mental world, at the same time that it represents an object or vista in the real world, or in an imagined universe. Every drawing is also an excavation into the drawer’s past and memory. John Berger describes this seminal merging of the object and the drawer him/herself: “It is the actual act of drawing that forces the artist to look at the object in front of him, to dissect it in his mind’s eye and put it together again; or, if he is drawing from memory, that forces him to dredge his own mind, to discover the content of his own store of past observations”” (90)

5.

In fact, every act of sketching and drawing produces three different sets of images:/the drawing that appears on the paper, the visual image recorded in my cerebral memory, and a muscular memory of the act of drawing itself. /All three images are not mere momentary snapshots, as they are recordings of a temporal process of successive perception, measuring, evaluation, correction and re-evaluation. A drawing is an image that compresses an entire process fusing a distinct duration into that image. A sketch is in fact a temporal image, a piece of cinematic action recorded as a graphic image.” (91)

6.

“The capacity to imagine situations of life is more important talent for an architect than the gift of fantasising space “ Aulis Blomstedt (114)

7.

Heidegger considers teaching even more difficult than learning: ‘Teaching is even more difficult than learning […] Not because the teacher must have a larger store of information, and have it always ready. Teaching is more difficult than learning because what teaching calls for is this: to let learn. The real teacher, in fact, lets nothing else be learned than – learning.”” (120)

8.

“One of the most demanding requirements of an architect is the capacity to sustain a sense of inspiration and freshness of approach for several years, and sometimes through several successive alternative projects.” (084)

9.

Architecture does not invent meaning; it can move us only if it is capable of touching something already buried deep in our embodied memories. (136)

10.

“My confidence in the future of literature consists in the knowledge that there are things that only literature can give us, by means specific to it, Italo Calvino in his Six Memos for the Next Millennium;

In my view, the task of architecture is to maintain the differentiation and hierarchical and qualitative articulation of existential space. Instead of participating in the process of further speeding up the experience of the world, architecture has to slow down experience, halt time, and defend the natural slowness and diversity of experience. Architecture must defend us against excessive exposure, noise and communication. Finally, the task of architecture is to maintain and defend silence. (150)

You must be logged in to post a comment.