Sitting in a recent review for campus design, I kept using the phrase ‘space between buildings’ repeatedly. After the review i was just wondering if I overemphasised this notion, as we know how teachers can hold to only few things dearly. Just to cross check myself, I tried to think of two examples to support my own thought.

01.

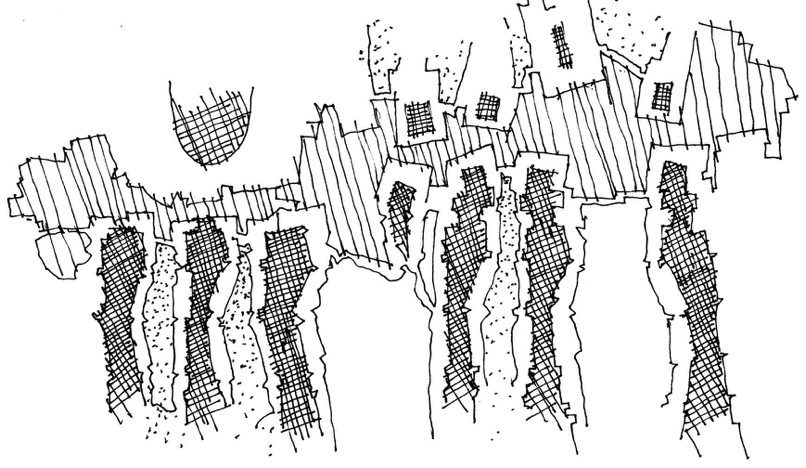

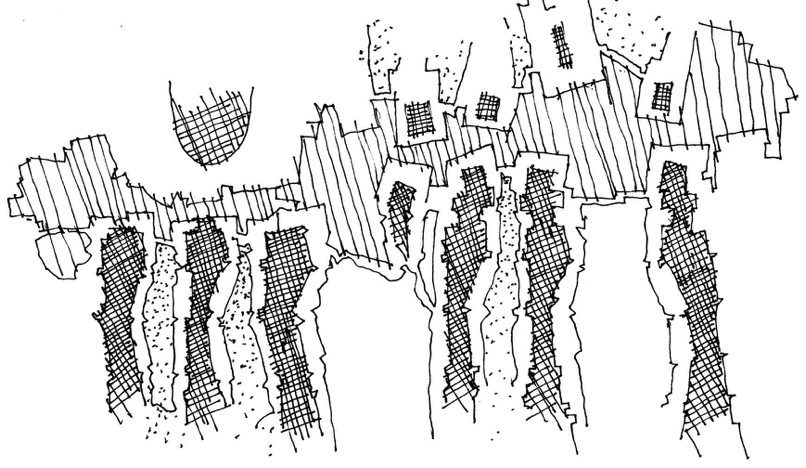

The drawing below was part of early process for the proposal for Nalanda University Competition. I was a member of the Hundredhands team which participated then. The particular intent of the drawing is to take the figure/ground drawing to the next level. Different density of hatches depict different types of in-between-unbuilt space in the project. The parallel line hatch depicts the central spine along which the faculty buildings and the major public buildings (library, dining, etc) were organised. The cross hatch highlights the intimate space within each faculty department zone (academics + hostels + faculty housing) .

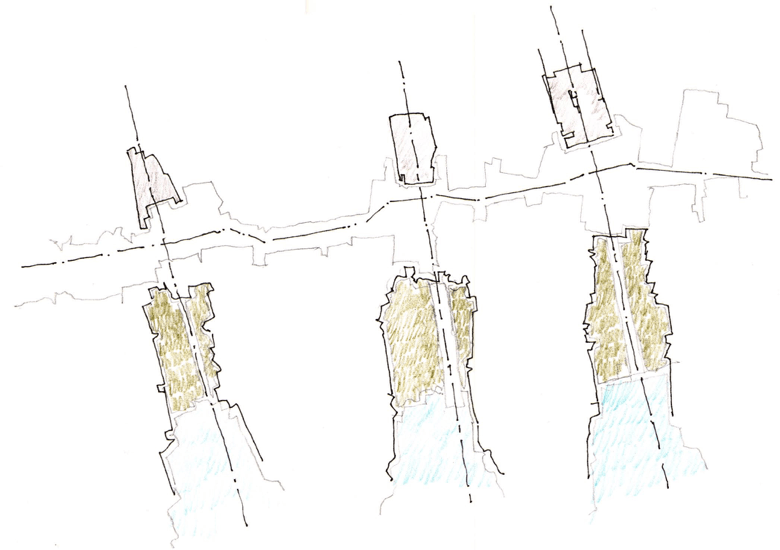

In this other drawing below for the competition, I tried to mark the public buildings ( library, dining, etc) along the spine, which would release to a large vista of open space. A strategy to both control and establish the scale of the campus and also to interrupt the length of the spine to articulate its linear experience.

02.

I am sharing an extract here from Paul Goldberger’s impeccable explanation of the University of Virginia’s central lawn and the buildings around it. This is from the book “Why Architecture Matters”, a must read anyway. The point to select this piece is not only for the relevance, but also for the delicate and precise description of an architectural space, which is so difficult to describe because of its tectonic nature.

.

“Designed when (Thomas) Jefferson was seventy four, the “academic village” as he liked to call it, consists of two parallel rows of five classical houses, called pavilions, connected by low, colonnaded walkways, which face each other a wide, magnificently proportioned grassy lawn. At the head of the lawn, presiding over the entire composition, is the Rotunda, a domed structure he based on the Pantheon in Rome.

…

The whole place is a lesson, not just in the didactic sense of the classic orders, but in a thousand subtler ways as well. Ultimately the University of Virginia is an essay in balance – balance between the built world and the natural one, between the individual and the community, between the past and the present, between order and freedom. There is order to the buildings, freedom to the lawn itself – but as the buildings order and define and enclose the great open space, so does space makes the buildings sensual and rich. Neither the buildings nor the lawn would have any meaning without the other, and the dialogue they enter into is a sublime composition.

The lawn is terraced, so that it steps down gradually as it moves away from the Rotunda, adding a whole other rhythm to the composition. The lawn is a room, and the sky is the ceiling; I know of few other outdoor places anywhere where the sense of architectural space can be so intensely felt.

In Jefferson’s buildings, there are other kinds of balances as well, between the icy coolness of the white-painted stone and the warm redness of the brick, between the sumptuousness of the Corinthian order and the restraint of the Doric, between the rhythm of the columns, marching on and on down the lawn, and the masses of the pavilions. In the late afternoon light all this can tug at your heart, and you feel that you can touch that light, dancing on those columns, making the brick soft and rich. There is awesome beauty here, but also utter clarity. It becomes clear that Jefferson created both a total abstraction and a remarkably literal expression of the idea. Architecture has rarely been as sure of itself, as creative, as inventive and as relaxed as it is here” ( Pages 13-15)

.

Some images for below for reference ( Source

Archdaily Classics, Photo Credits : Larry Harris)

.

.

.

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.