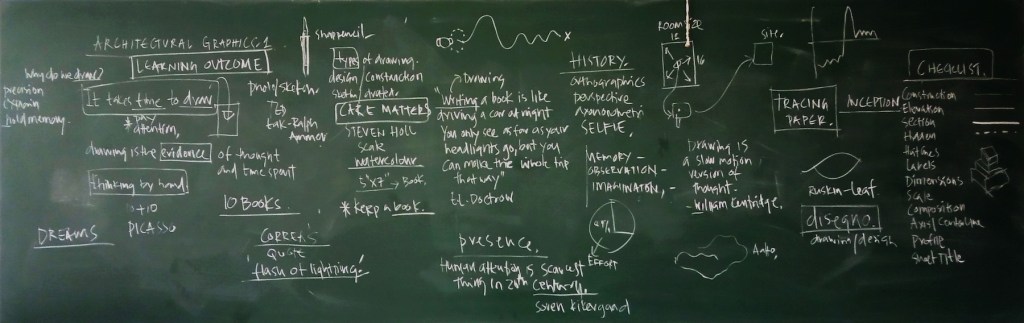

After a cycle of teaching online, i am rediscovering the nuances of the blackboard. It has a certain slowness, and allows to grow thoughts collectively as the class proceeds. It traces the emphasis and the hesitations of the teacher, simultaneously. It is an evidence of overlapping thoughts and time, unlike a digital presentation which displaces time. Here the attempt was to summarise the learning outcome of the first semester drawing course. It traced all the things we spoke about the need to ‘draw’. There is a certain pleasure to look at the final mess, like the one we have when we cook our own food.

Notes : Learning from Ekalavya

Reading notes from the essay ‘Learning from Ekalvya’ on architectural education by Charles Correa

Correa brilliantly argues about architectural education in this essay : He broadly categorises two types of studios : guru studio and distancing studios. In guru studio “The master, coming to your desk, would pick up a thick grease pencil and draw a bold line, changing things radically: the proportions, the cornice, the depth of the shadows, whatever. “Not this—this!” And you learned because you trusted his judgment, you entered the gestalt of his world. ” In the distancing studio, the students learns from their own process and judgement beyond the ‘idiosyncrasy’ of the guru studio. Correa argues that a school needs a good balance between these two types “The system would also allow a school to use its faculty to much better advantage—because it would make explicit the differences between the two types of studio, permitting each of them to be run with minimal cross- sniping. So that gurus who have their own idiosyncratic and intuitive design skills could return to the atelier model of teaching without being accused of reckless brainwashing, while those teachers that run the distancing studios would not be criticized for not being “designers,” or “creative” enough, and so forth.” One of the sharpest sentences from the essay (and thus the story of Ekalavya reference) is that “This is why the presence, however hallucinatory, of the guru is so important. Through our trust in him, we teach ourselves.”

And there is another sharp observations on our expectation from students from design studio :”..on the contrary, students (regardless of any inherent aptitude for the astonishing mix of analytic, synthetic and topologic skills that make up the design process) are compelled to take such a studio every semester, for five continuous years— and it is always the heavyweight in their schedule, preempting enormous quantities of time and energy. Each semester these unhappy students are presented with brand-new problems, often in complicated and subtle contextual situations, and then asked to come up with new and brilliant responses, possibly expressed in an architectural syntax of their own invention. In the entire hisory of our profession, very few architects have managed to pull that one off— even once in their lifetime! Yet we demand this of each student, in each design studio. The result: dismay and frustration (and at several universities, among the highest stress rates of all departments) “

This essay is from the book “The Education of the Architect : Historiography, Urbanism, and the Growth of Architectural Knowledge” edited by Martha Pollak. It is available in open access format from MIT Press.

Drawing with care

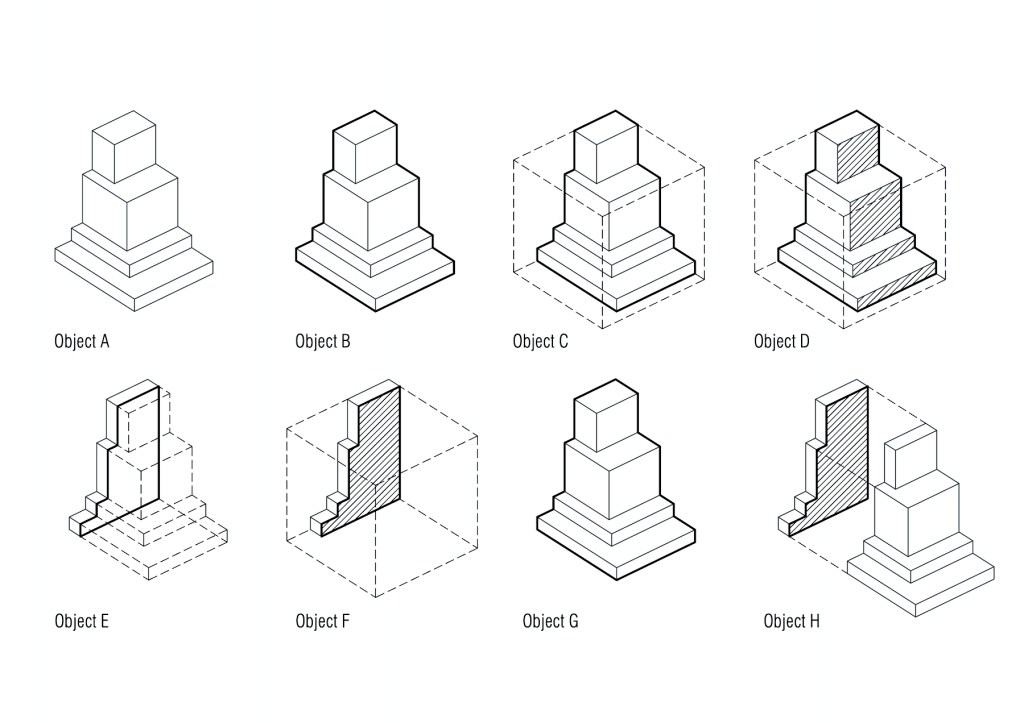

I have been teaching basic drawing course (technical drafting to be precise) skills for first year students for a few years now. Each time I teach, it is a great reminder to myself saying one needs to draw with ‘care’ – and thats all matters. The ‘care’ gets manifested in the drawings implicitly. It is this ‘care’ which translates into actual construction too. I am looking for new ways in the class to emphasis this point. Here is a drawing i made for this week’s class to make this point. The difference between object A and B is just an extra bold silhouette. It takes only 10 % of extra time to finish the drawing but then makes the drawing read many times better. The extra line itself doesn’t matter per se, but the time and mindset it takes to take a bit extra ‘care’ is what matters. Drawing as carrier of ‘care’ and ‘attention’.

In the seminal book ‘Why Architects Draw’ Edward Robbins makes this observation while talking about Moneo’s drawings and design process ” This emphasis on the craft of drawing comes from the belief that craft must be a part of the whole process of design and building. This care for craft and for beauty must start at the very beginning of the process of design and be kept all the way through that process. As drawing is essential to design, it too must always reveal a sense of craft and a sense of the qualities of beauty that in the end one wants one’s building to show.”

Drawing 09

Splitting and Branching – possible fragmentation of scale on the threshold of accretive and ordered.

Genre / Generic : 02

After i posted this previous post, Aabid dropped me a message asking what i meant by the last sentence, “Architecture can become more inclusive, by understanding what rhymes with the everyday, ordinary, familiar and relevant.” On rereading, it also seemed to me a bit of disconnect to what i was saying earlier on how to bend the genres of modernism and vernacular. I have been thinking of his question and I thought i could explain it a bit more.

Does architecture always has to only rhyme with the unique and the sophisticated (say Modernism), crafted and the refined (like the vernacular)? Can it also rhyme with the ‘everyday, ordinary, familiar and relevant’ and just be rudimentary? – Like this house in my neighbourhood in Mysore has this metal mesh box built on the terrace to house its ever-growing garden. Can i rhyme with a condition like this too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.