The brilliant book Writing Analytically (David Rossenwasser and Jill Stephen), addressed at students of writing course, starts with the chapter : Analysis – What it is and What it does. The book defines writing as “recording our thoughts in search of understanding” and “More than just a set of skills, analysis is a frame of mind, an attitude toward experience. It is a form of detective work that typically pursues something puzzling, something you are seeking to understand rather than something you are already sure you have the answers to”. These are the five moves formulated in the first chapter. Below is a very short extract of the same:

Move 1: Suspend Judgment

Suspending judgment is a necessary precursor to thinking analytically because our tendency to judge everything shuts down our ability to see and to think.

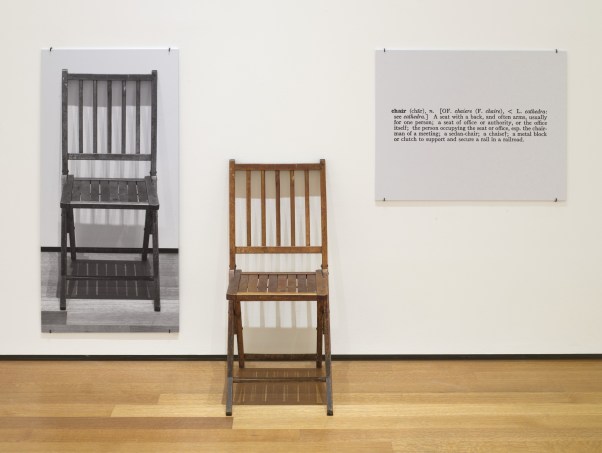

Move 2: Define Significant Parts and How They’re Related

Whether you are analyzing an awkward social situation, an economic problem, a painting, a substance in a chemistry lab, or your chances of succeeding in a job interview, the process of analysis is the same :

Divide the subject into its defining parts, its main elements or ingredients.

Consider how these parts are related, both to each other and to the subject as a whole.

Move 3: Make the Implicit Explicit

One definition of what analytical writing does is that it makes explicit (overtly stated) what is implicit (suggested but not overtly stated), converting suggestions into direct statements.

Move 4: Look for Patterns

We have been defining analysis as the understanding of parts in relation to each other and to a whole, as well as the understanding of the whole in terms of the relationships among its parts. But how do you know which parts to attend to? What makes some details in the material you are studying more worthy of your attention than others?

Look for a pattern of repetition or resemblance.

Look for binary oppositions

Look for anomalies—things that seem unusual, seem not to fit.

Move 5: Keep Reformulating Questions and Explanations

Analysis, like all forms of writing, requires a lot of experimenting. Because the purpose of analytical writing is to figure something out, you shouldn’t expect to know at the start of your writing process exactly where you are going, how all of your subject’s parts fit together, and to what end. The key is to be patient and to know that there are procedures—in this case, questions—you can rely on to take you from uncertainty to understanding.

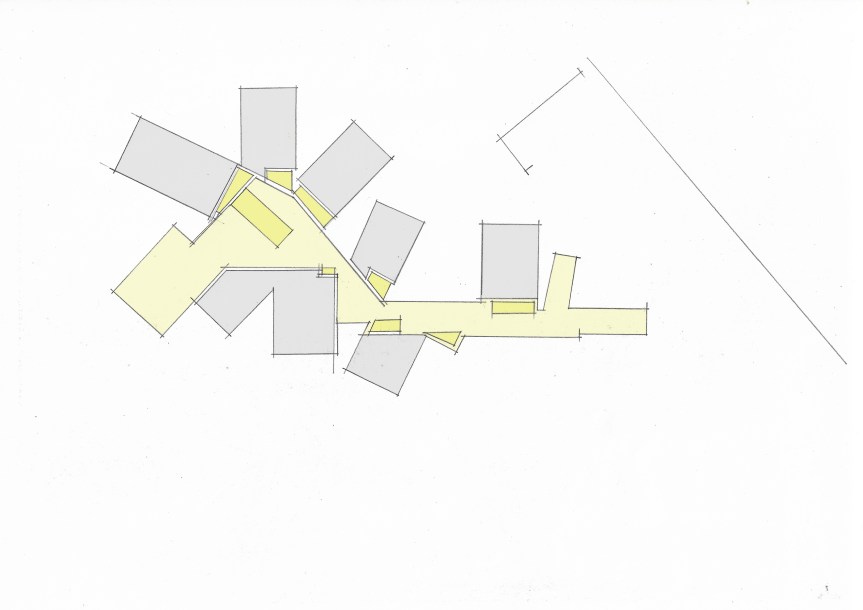

I thought applying this in studying architectural precedents in the form of diagramming/analysis for the House at Pego designed by Alvaro Siza. I was familiar this plan for a long time, and kept going back many times. May be it was the accretive nature that made me incline towards this composition. Then one day i though of just tracing it. It revealed new meanings, which was not visible to me until i attempted drawing over it.

During the course of our post graduate program we were fortunate to have had

During the course of our post graduate program we were fortunate to have had

You must be logged in to post a comment.