I recently bought a car, and one of the pet peeves I discovered was listening to music in a closed space (unlike with headphones). I started making a playlist for my car, and after almost 2 years and 24 songs later, I have a slow-cooked personal playlist that can make and change my mood.

During my school and early college days, I had the delight of making playlists on cassettes. Because one couldn’t afford to buy all the albums, one had to carefully select songs and go to a cassette shop, either choosing a 60-minute or 90-minute cassette and filling it with favorite songs. The logistics, availability, and cost of making the playlist made it precious by default. The playlist was a collection—a place of refuge to spend time with things that were very dear to you.

One of the recent songs I added was ‘O Sanam’ by Lucky Ali. I serendipitously stumbled upon that song recently and had forgotten the calmness it brought me when I listened to it a decade and a half ago. Listening to the song now brings back those feelings. I am enjoying my 24-ish songs so warmly. When I am distracted, I play the list in the order I have decided; if I want to have some fun, I just shuffle—a delight when you don’t know which is your next song.

Why write about playlists now, and that too when they are easy to make? Just right-click and add it to a playlist. Yes, that’s the point: it’s easy, and it is too easy. You can add a thousand songs to a list and make a hundred lists on ten devices with just a few clicks. You don’t have to find a cassette shop that has stocked all A R Rahman albums in Tamil version, and if you found one, it would become a sanctuary.

Now, the playlist has to become a filter to resist the overloaded world. If I am not wrong, it is philosopher Søren Kierkegaard who said we are tranquillized by the trivial.

Why is this important? It is important because I can get overwhelmed even if I have six tabs open in my browser. (One of my students had 24 tabs open, and I think she had another window with more tabs open, which she didn’t show me.) This is a true reflection of our time.

Playlists can become tools of resistance. Now I will make this relevant by placing it in the context of this blog, where topics are generally related to architecture (though I hope to deviate when needed). The playlist should be very personal—so personal that you should not share it either. I will follow that here and not share my full playlist, not because it is a secret, but because it is personal and not relevant to anyone without the meaning I have attached to it over time. Make a list of references and build a fort around it. Don’t let in or let go of ideas or thoughts without strict scrutiny. When one’s position is attacked, take refuge in the playlist and see if the attack is constructive and borrow something from it.

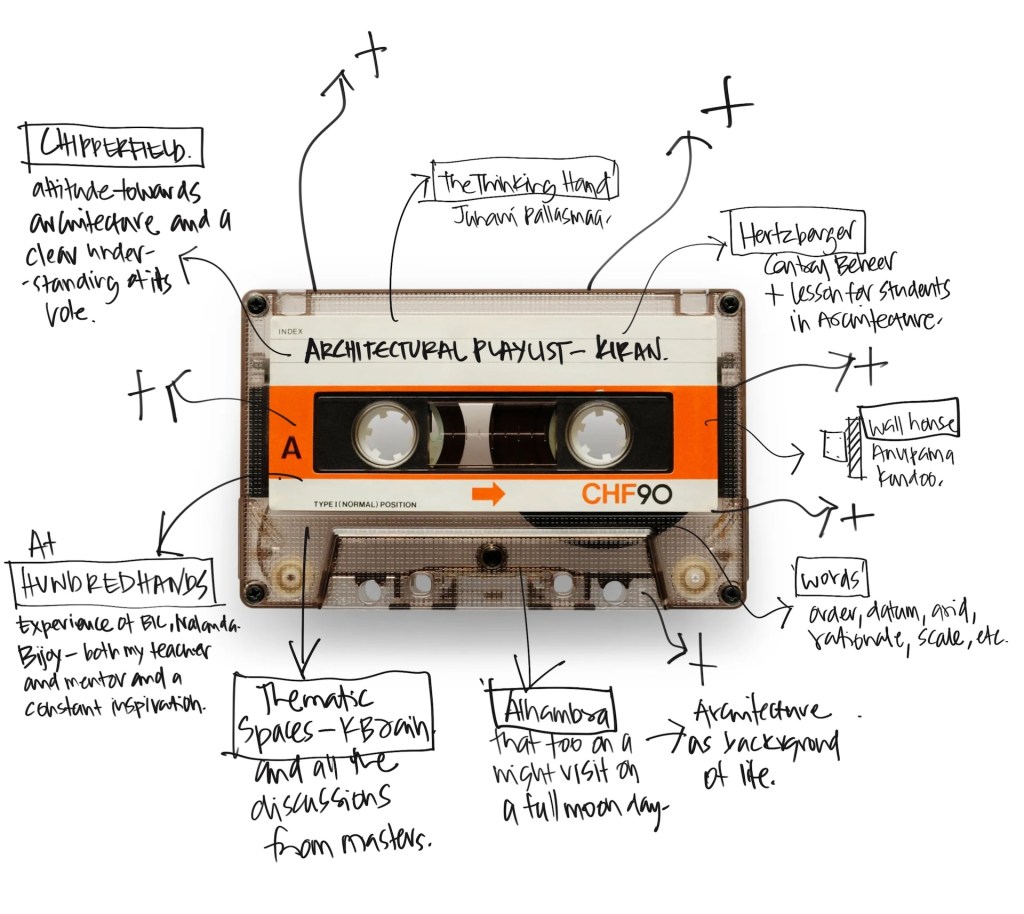

My playlist will contain projects I visited and relished (like Alhambra in Spain—a night visit on a full moon day), projects I adore analyzing (such as Wall House by Anupama Kundoo), words that thrilled me as a student (like order), books I wish I had known in my first year—not in my final year or master’s (Lessons for Students in Architecture by Herman Hertzberger), books I wish I could rediscover and want to read freshly every time (The Thinking Hand by Juhani Pallasmaa), definitions or quotes on theory, drawings, and design; memories of being in architecture and being moved calmly by it, memories and generosity of my teachers and mentors, specific dialogues with friends and students, a little detail I admire, a material finish I enjoy, the unique smell of my grandfather’s grocery store at my native place, etc.

My playlist consists of things I resonate deeply with, not just a shallow list of things I like (that is easy). One needs to dig deep. I am not talking about bookmarks in ArchDaily, saved items on Pinterest and Instagram. I am talking about things that hold significant value in one’s own journey. This playlist needs to be visible or accessible on an everyday basis.

Being a teacher, what I teach becomes a sort of playlist in itself. I have found other uses for the list as a teacher. I decide the precedent studies in class, so I can be sharp about my argument and it can become a common ground for discussions in class. I think young architects can also benefit from this, as their Instagram (like mine) constantly bombards them with interesting and useful information at an unfathomable rate. Social media has the nature to make us feel inadequate. It is never enough. Anne Lamott beautifully says, “Try not to compare your insides to other people’s outsides. It will only make you worse than you already are.” Social media gives this feeling on a platter. I try to use the playlist as a piece of resistance to that.

I casually made a note on the differences between case studies and precedents in a lecture. Case studies are made out of need—to tackle a problem or situation. Precedents, I think, are perennial, long-term. That list can bring a moment of calmness and joy when one engages with it. When one is lost, it can become a guidepost to not lose hope and affirm one’s pursuit in architecture.

Note : Used AI help only to check grammar (which seems like a very useful tool – when used carefully)

You must be logged in to post a comment.